Ralph Adams Cram and His Shaping of American Urban Identity Through Sacred Architecture

Across the American urban landscape, the legacy of Ralph Adams Cram endures not only in stone and stained glass but in the cultural and civic life of neighborhoods that have grown around his churches. These buildings, often constructed in the Gothic Revival tradition, serve as architectural anchors in cities like Detroit, Jersey City, and Princeton, where Cram’s vision of sacred space continues to influence both the skyline and the soul of the community.

The Signature of a Master: Gothic Revival in America

Cram was not just an architect; he was a cultural theorist who believed that architecture had a moral and spiritual purpose. His preference for Gothic Revival architecture was not a mere stylistic choice, it was an intentional return to what he viewed as a spiritually rich and socially unifying form. In an era of increasing industrialization and secularization, Cram’s churches were designed to restore a sense of transcendence, order, and civic pride.

His use of soaring vaults, pointed arches, and intricately carved facades reflected a deep belief in the transformative power of beauty. These structures weren’t just places of worship; they were meant to shape the character of neighborhoods and cities.

Three Churches, One Vision

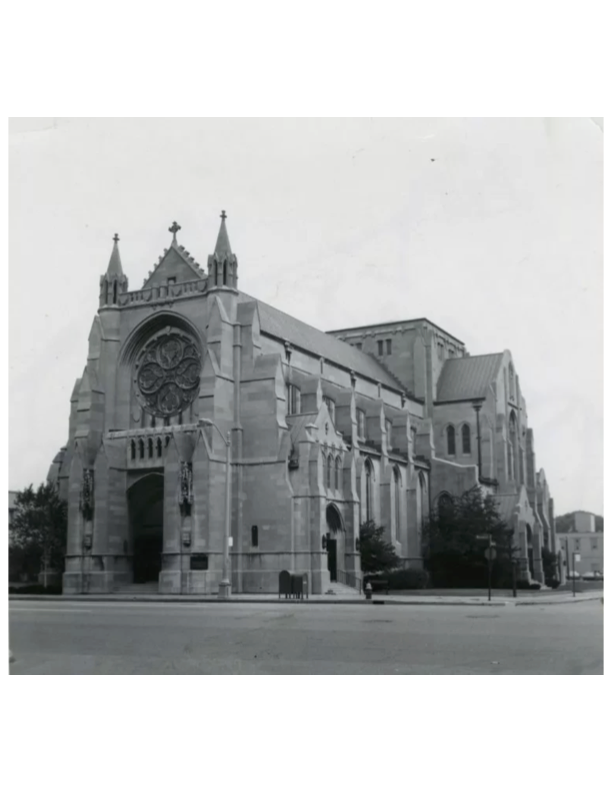

Cathedral Church of St. Paul, Detroit (1908). This monumental limestone structure in Detroit exemplifies Cram’s vision of ecclesiastical architecture as a civic force. The Cathedral Church of St. Paul’s cruciform plan and ribbed vaulting elevate it above the urban landscape both literally and symbolically. It projects permanence and stability, qualities that remain essential in a city that has weathered economic and demographic upheavals.

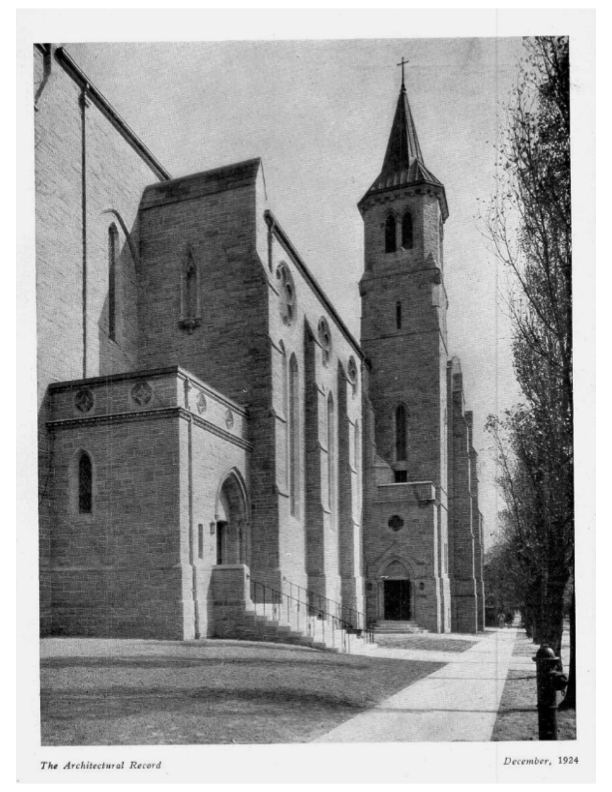

Sacred Heart Church, Jersey City (1922). In Jersey City’s Greenville neighborhood, Sacred Heart Church exemplifies Gothic Revival’s power to inspire and unify. Its vibrant polychrome interior and richly detailed stonework create a sensory experience that invites reflection. More than a church, Sacred Heart has become a visual and spiritual landmark in a neighborhood where heritage properties are being rediscovered and restored.

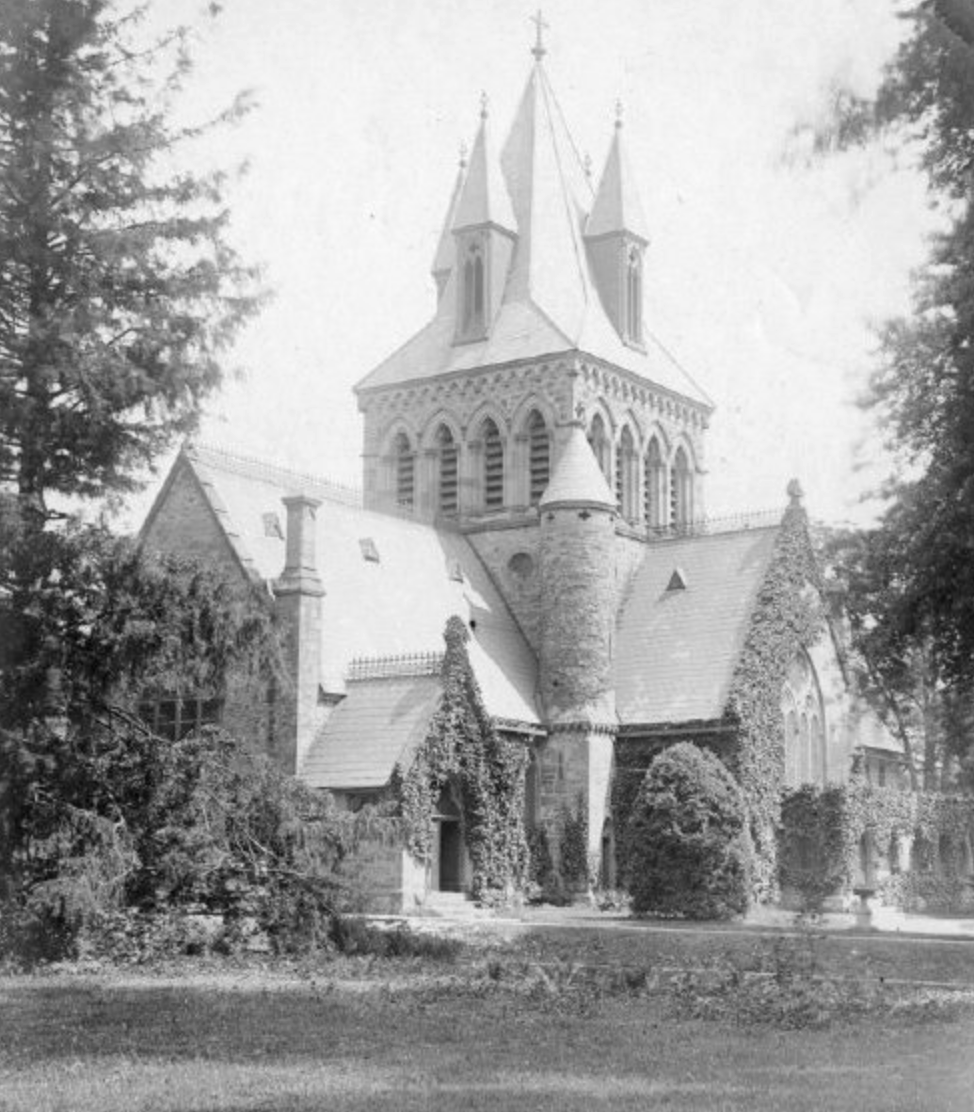

Trinity Church, Princeton (1913). While smaller in scale and built with fieldstone rather than limestone, Trinity Church in Princeton carries the same architectural DNA. Its collegiate Gothic elements harmonize with the town’s academic setting, creating a seamless integration between sacred space and scholarly life. As with all of Cram’s works, the architecture itself encourages contemplation, dialogue, and community.

Shared Elements That Define Their Impact

Despite their geographic and cultural differences, all three churches share key features that express Cram’s ideals:

Verticality and Light: These buildings pull the eye and the spirit upward. The extensive use of stained glass allows colored light to animate the interiors, reinforcing a sense of awe and elevation.

Structural Expression: The ribbed vaults and arches are not merely decorative but convey the logic of their construction, a principle inherited from medieval architecture that underscores integrity and truth.

Material Symbolism: Limestone and fieldstone were chosen not just for durability, but for their ability to communicate rootedness, age, and a sense of belonging to the landscape.

More Than Monuments: Community Roles

These churches transcend their religious function. In every case, the buildings have become centers for civic engagement, cultural programming, and social outreach. In Detroit, St. Paul’s hosts concerts and public events that reinforce its role as a civic gathering place. In Jersey City, Sacred Heart is being reimagined as a cultural cornerstone, its presence anchoring a wave of adaptive reuse projects in the historic Greenville area. In Princeton, Trinity serves not only worshippers but also academics and artists, creating space for lectures, concerts, and interfaith dialogue.

Their continued relevance demonstrates the foresight of Cram’s vision: that sacred architecture could—and should, play an enduring role in the life of American cities.

Architecture and Civic Identity

Recognizing architects like Ralph Adams Cram is not just about remembering his buildings, it’s about honoring the ways these structures have molded cities. These buildings matter not just aesthetically, but socially and culturally. By promoting reuse of these spaces, cities affirm the values embedded in their walls: continuity, craftsmanship, and civic responsibility.

The Future of the Past

In a time when many former churches are being repurposed into nightclubs, residences, and offices, the legacy of Cram’s work offers a compelling argument for thoughtful reuse. His churches are more than relics; they are living monuments that continue to shape the neighborhoods around them. From Detroit to Jersey City to Princeton, Cram’s architecture reminds us that beauty, purpose, and community are not separate goals, but are deeply interconnected. And in the hands of a visionary architect, a building can do more than its original congregational use. It can help define the soul of a city.