Ralph Adams Cram and His Shaping of American Urban Identity Through Sacred Architecture

Across the American urban landscape, the legacy of Ralph Adams Cram endures not only in stone and stained glass but in the cultural and civic life of neighborhoods that have grown around his churches. These buildings, often constructed in the Gothic Revival tradition, serve as architectural anchors in cities like Detroit, Jersey City, and Princeton, where Cram’s vision of sacred space continues to influence both the skyline and the soul of the community.

The Signature of a Master: Gothic Revival in America

Cram was not just an architect; he was a cultural theorist who believed that architecture had a moral and spiritual purpose. His preference for Gothic Revival architecture was not a mere stylistic choice, it was an intentional return to what he viewed as a spiritually rich and socially unifying form. In an era of increasing industrialization and secularization, Cram’s churches were designed to restore a sense of transcendence, order, and civic pride.

His use of soaring vaults, pointed arches, and intricately carved facades reflected a deep belief in the transformative power of beauty. These structures weren’t just places of worship; they were meant to shape the character of neighborhoods and cities.

Three Churches, One Vision

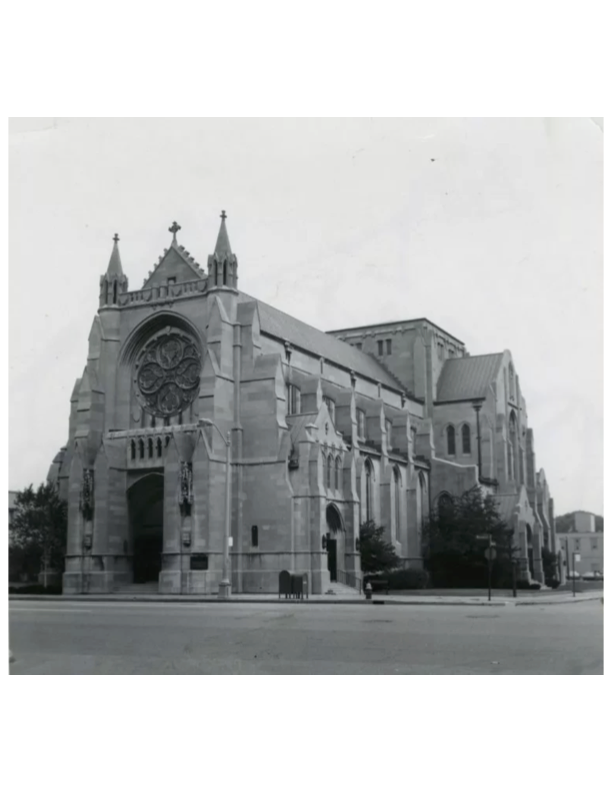

Cathedral Church of St. Paul, Detroit (1908). This monumental limestone structure in Detroit exemplifies Cram’s vision of ecclesiastical architecture as a civic force. The Cathedral Church of St. Paul’s cruciform plan and ribbed vaulting elevate it above the urban landscape both literally and symbolically. It projects permanence and stability, qualities that remain essential in a city that has weathered economic and demographic upheavals.

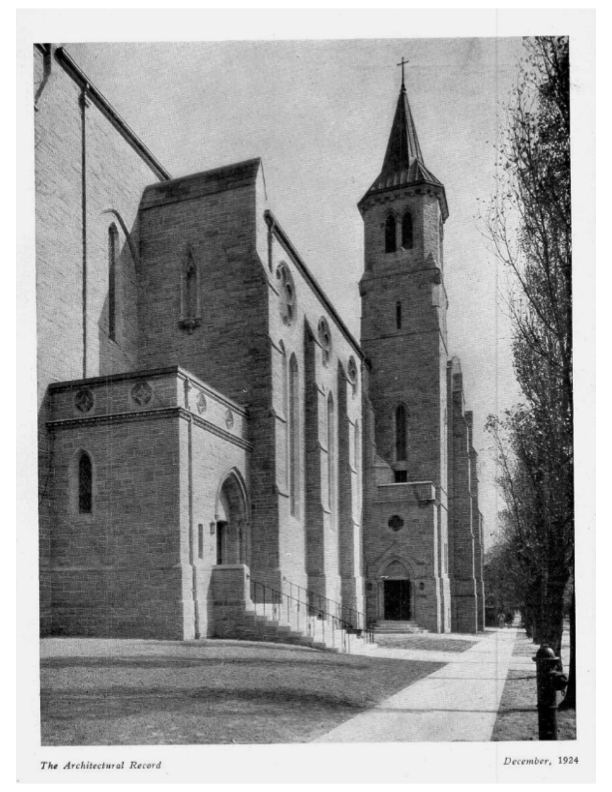

Sacred Heart Church, Jersey City (1922). In Jersey City’s Greenville neighborhood, Sacred Heart Church exemplifies Gothic Revival’s power to inspire and unify. Its vibrant polychrome interior and richly detailed stonework create a sensory experience that invites reflection. More than a church, Sacred Heart has become a visual and spiritual landmark in a neighborhood where heritage properties are being rediscovered and restored.

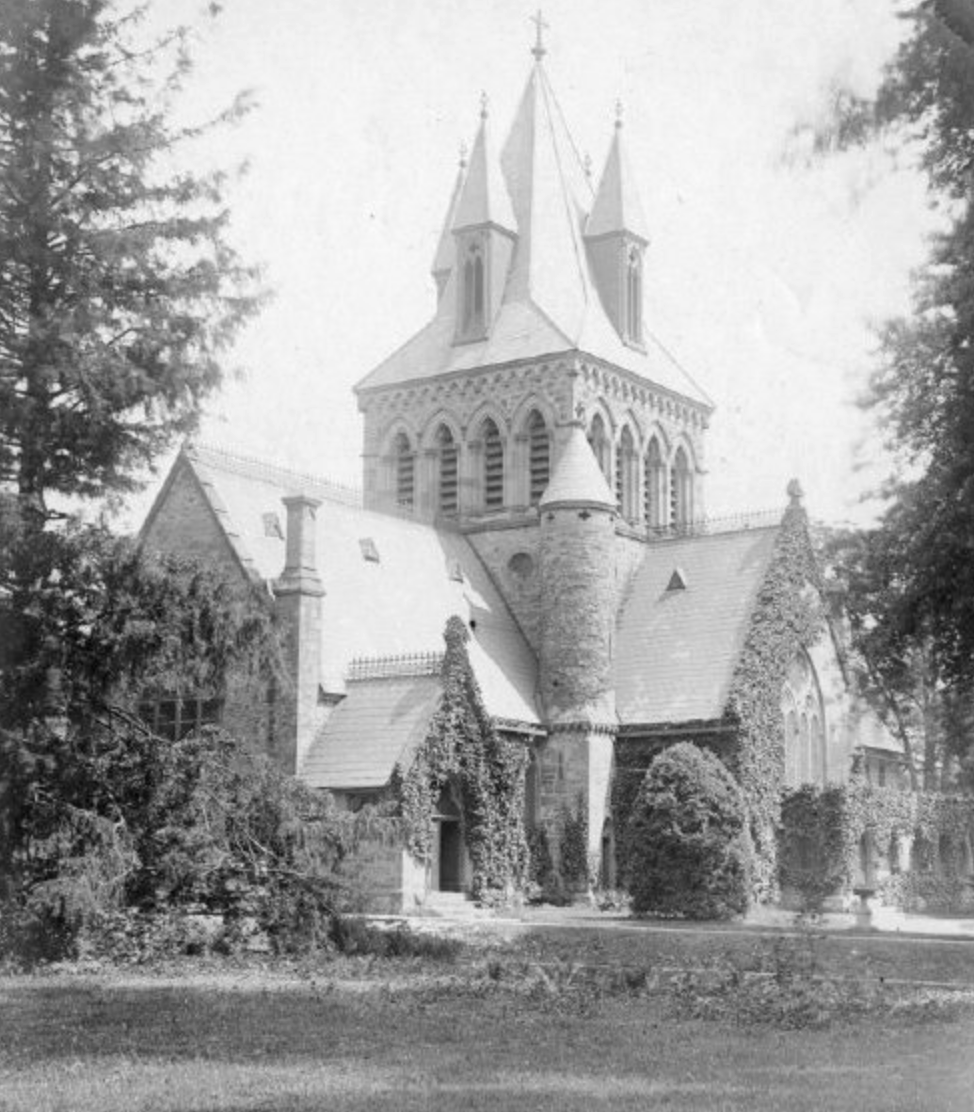

Trinity Church, Princeton (1913). While smaller in scale and built with fieldstone rather than limestone, Trinity Church in Princeton carries the same architectural DNA. Its collegiate Gothic elements harmonize with the town’s academic setting, creating a seamless integration between sacred space and scholarly life. As with all of Cram’s works, the architecture itself encourages contemplation, dialogue, and community.

Shared Elements That Define Their Impact

Despite their geographic and cultural differences, all three churches share key features that express Cram’s ideals:

Verticality and Light: These buildings pull the eye and the spirit upward. The extensive use of stained glass allows colored light to animate the interiors, reinforcing a sense of awe and elevation.

Structural Expression: The ribbed vaults and arches are not merely decorative but convey the logic of their construction, a principle inherited from medieval architecture that underscores integrity and truth.

Material Symbolism: Limestone and fieldstone were chosen not just for durability, but for their ability to communicate rootedness, age, and a sense of belonging to the landscape.

More Than Monuments: Community Roles

These churches transcend their religious function. In every case, the buildings have become centers for civic engagement, cultural programming, and social outreach. In Detroit, St. Paul’s hosts concerts and public events that reinforce its role as a civic gathering place. In Jersey City, Sacred Heart is being reimagined as a cultural cornerstone, its presence anchoring a wave of adaptive reuse projects in the historic Greenville area. In Princeton, Trinity serves not only worshippers but also academics and artists, creating space for lectures, concerts, and interfaith dialogue.

Their continued relevance demonstrates the foresight of Cram’s vision: that sacred architecture could—and should, play an enduring role in the life of American cities.

Architecture and Civic Identity

Recognizing architects like Ralph Adams Cram is not just about remembering his buildings, it’s about honoring the ways these structures have molded cities. These buildings matter not just aesthetically, but socially and culturally. By promoting reuse of these spaces, cities affirm the values embedded in their walls: continuity, craftsmanship, and civic responsibility.

The Future of the Past

In a time when many former churches are being repurposed into nightclubs, residences, and offices, the legacy of Cram’s work offers a compelling argument for thoughtful reuse. His churches are more than relics; they are living monuments that continue to shape the neighborhoods around them. From Detroit to Jersey City to Princeton, Cram’s architecture reminds us that beauty, purpose, and community are not separate goals, but are deeply interconnected. And in the hands of a visionary architect, a building can do more than its original congregational use. It can help define the soul of a city.

Restoring Light: A Journey Through Time at Hiemer & Company Stained Glass Studio

Hiemer & Company Stained Glass Studio, Clifton, NJ

A few weeks ago, my business partner and I stepped into the luminous world of Hiemer & Company Stained Glass Studio in Clifton, New Jersey, to inspect the painstakingly restored stained-glass panel from Sacred Heart Church, one that was tragically shattered in a fierce windstorm last year. As sunlight danced across the workshop's vibrant fragments, casting jewel-toned patterns on the worn wooden floors, I couldn't shake the profound sense of history pressing in around us. In that space of quiet intensity, where color meets craft, it felt less like a repair job and more like mending a thread in the fabric of time itself.

What unfolds daily at Hiemer's isn't mere restoration; it's a reverent conversation spanning generations of skilled hands. After a full year of meticulous work, we watched as artisans pieced together the broken glass, each curve aligned by seasoned eyes, every lead strip repositioned with surgical care. It was a powerful reminder of why we pour our hearts into historically respectful adaptive re-use development. This is the essence of "doing it right", a craft too vital for amateurs or armchair enthusiasts tinkering in clubhouses. It's about honoring the past with the precision it deserves.

A Studio Rooted in History

Hiemer & Company Stained Glass Studio's story reads like a chapter from an old masterwork, beginning in the shadow of the Great Depression. In the early 1930s, Edward W. Hiemer and his father, Georg, both honed in the rigorous traditions of Munich, Germany, founded their firm in Columbus, Ohio. Fresh from apprenticeships at the renowned Von Gerichten Studios, they refused to let economic hardship snuff out their European heritage. When Von Gerichten shuttered its doors, the Hiemers stepped up, with Edward steering the business side and Georg channeling his genius into design.As America's sacred spaces boomed in the mid-20th century, the family packed up for Paterson, New Jersey, drawn by commissions from the Catholic Church. Their work soon graced churches and monasteries from Boston to Washington, D.C., becoming synonymous with ecclesiastical artistry. By 1950, they settled in Clifton, where the studio thrives today under the stewardship of its fourth generation, a testament to resilience and unwavering commitment.

A Sacred Connection with Jersey City

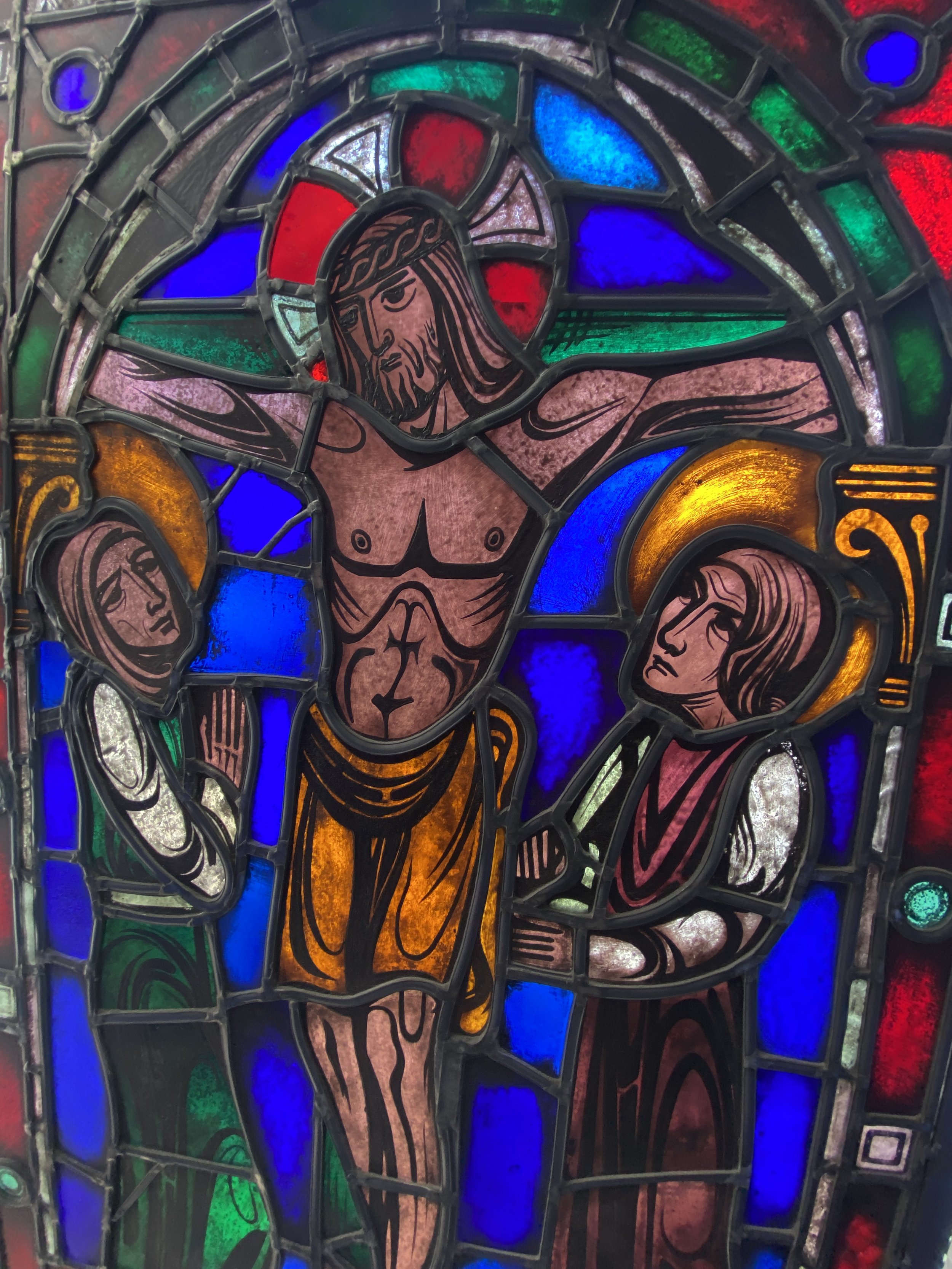

The Crucifixion, Hiemer and Company, 1948-53

The bond between Hiemer & Co. and Jersey City's Sacred Heart Church dates back to the 1940s, when Dominican friars entrusted the studio with crafting lancet windows for the priory chapel. What started as a single project blossomed into a lifelong partnership, shaping the church's ethereal glow for decades.The postwar era marked a creative pinnacle, with artists like Jacob Renner and Simon Berasaluce, the latter a Spanish virtuoso of faceted glass, infusing the work with bold innovation. Their techniques added depth and drama, blending medieval reverence with modernist flair. Sacred Heart's windows from this time stand as jewels among New Jersey's mid-century ecclesiastical treasures, whispering stories of faith through every shaded facet.

A Legacy Carried Forward

The flame passed steadily: After Edward ("Edi") Hiemer's death in 1969, his son Gerhard ("Gerry") Hiemer expanded the studio's horizons. Then came Judith Hiemer Van Wie, Gerry's daughter, who blended formal training, a business degree from Bryant University, design studies at Parsons, with hands-on apprenticeship in the family trade. Today, Judith and her husband, James Van Wie, helm the operation as proud fourth-generation stewards. Judith dives into liturgical design and fresh commissions, while James champions restorations, grounding every project in both artistic soul and practical wisdom. Whether resurrecting a Victorian-era panel or illuminating a modern sanctuary, they ensure the work resonates with spiritual depth and structural integrity.

Restoration as Shared Purpose

Our time at Hiemer's crystallized how our ethos mirrors this family's dedication. For us, restoration isn't about cloning the past, it's about weaving it into the present, safeguarding a community's soul through its built heritage. Reviving Sacred Heart's stained glass has been a year-long marathon of meticulous documentation, fragment-by-fragment repair, and collaborative expertise from artisans, historians, and conservators. It's a symphony of cross-referenced research and top-tier professionals, each note tuned to authenticity. Now, with the panels restored, when sunlight filters through once more, painting the stone walls in hues of divine inspiration, it will transcend mere fixes. It will reignite a century-spanning dialogue of art, faith, and craftsmanship. And in that glow, we'll see irrefutable proof: When we cherish history with intention, it doesn't just endure, it illuminates the path ahead.

A Florida-Style Affordable Housing Law Could Unlock Stagnant Transit Sites in New Jersey

Walk along MLK Drive in Newark or Main Street in East Orange, and you’ll see the same pattern repeating itself: one-story commercial strips, shallow parking lots, and vacant parcels sitting atop some of the best transit infrastructure in the country. Newark Penn Station connects directly to Amtrak, PATH, and both NJ Transit rail and light rail. East Orange has two Morris and Essex Line stations—East Orange and Brick Church—that run straight into Newark and New York. Yet despite this connectivity, the surrounding corridors remain dramatically underbuilt relative to their potential.

A Florida-style Live Local Act affordable housing law would change that. By pairing by-right approvals for mixed-income housing on commercial land with minimum development capacity, mandatory parking reductions near transit, and a uniform property-tax tool for income-restricted units, New Jersey could make these corridors viable for small and mid-sized developers—not just a handful of large players with the resources to negotiate rezonings parcel by parcel. A state law would make these requirements uniform statewide and not subject to the whims of bad-acting politicians.

Before and After: Transit Walksheds in Newark and East Orange

To visualize the impact, imagine two simple maps—each showing a 10-minute walkshed (roughly a half-mile radius) around key NJ Transit stations.

Current Conditions: Newark Penn Station (Before)

One-story commercial buildings cluster near Broad Street and McCarter Highway. Large surface parking lots dominate the station area. Many parcels are underutilized or vacant, despite direct service to Amtrak, PATH, and multiple rail and bus lines. Any serious redevelopment currently requires lengthy zoning changes or site-plan amendments.

With Reform: Newark Penn Station (After)

Mixed-use, mid-rise buildings—four to seven stories—line the streets around the station. Ground floors contain neighborhood retail and services, while upper floors combine market-rate and income-restricted housing secured for 30 years. Projects are administratively approved if they meet objective standards—no variances or rezonings required. Parking minimums are reduced or eliminated, reflecting proximity to transit.

Current Conditions: East Orange and Brick Church (Before)

Main Street and Freeway Drive are dominated by low-intensity uses, older retail pads, and excess parking. Despite strong commuter rail access, parcels remain locked in outdated commercial zoning with density caps and conventional parking mandates. Developers must seek rezonings to build mixed-use housing, creating uncertainty and expense.

With Reform: East Orange and Brick Church (After)

Shallow commercial parcels become viable for four- to seven-story mixed-use infill. Forty percent of units are income-restricted for at least 30 years, unlocking by-right status. Density and FAR minimums match the city’s highest allowed, ensuring projects can pencil without case-by-case negotiations. Parking requirements drop automatically near stations, cutting the cost of structured parking. Approvals shift from multi-year rezoning battles to straightforward administrative reviews.

How the Florida Live Local Act Works — and Why It Fits Newark and East Orange

By-right mixed use on commercial land with affordability

Florida requires cities to allow mixed-use or multifamily development by right on commercially or industrially zoned parcels if at least 40 percent of the units are income-restricted for 30 years. No separate zoning or land-use changes are required for use, density, or height when projects meet objective standards. For Newark and East Orange, this means corridors like Broad Street and Main Street could transition from strip retail to mixed-use housing quickly and predictably.

Minimum development capacity

Florida prohibits localities from capping density below the highest already allowed in their jurisdiction and sets a floor of at least 150 percent of the highest local floor area ratio. In East Orange, this could match or even exceed the scale of the Brick Church redevelopment. In Newark, it would align station-area projects with downtown densities without requiring individual negotiations.

Parking reform near transit

Florida mandates at least a 20 percent reduction in parking near major transit hubs, and full elimination of minimums inside designated transit-oriented districts. Newark Penn Station and Brick Church easily qualify. Structured parking is one of the largest cost drivers in mid-rise development; reducing or eliminating minimums can make the difference between feasible and infeasible.

A uniform property-tax tool for restricted units

Florida introduced a clear, statewide ad valorem exemption for the improvement value of newly constructed income-restricted units, certified by the housing agency. This baseline exemption reduces operating costs and complements—rather than replaces—negotiated PILOT agreements. For smaller Newark or East Orange infill projects, it would allow deals to close without complex, site-specific tax negotiations.

Immediate Impacts if New Jersey Adopted This Model

Unlocking commercial strips near transit: Main Street in East Orange and Broad Street in Newark would become natural targets for mixed-income infill, not rezoning battles.

Shorter timelines, lower risk: Administrative approvals for qualifying projects remove years of uncertainty and legal fees, allowing smaller firms to participate.

More housing where infrastructure already exists: Both cities have stations, buses, and established urban grids. A Florida-style statute directs growth to these places without additional public infrastructure costs.

Guaranteed affordability: The 40 percent requirement locks in long-term affordability while allowing market-rate units to support mixed-income development.

Why Newark and East Orange Are Ideal Test Cases

Newark and East Orange already have high-frequency rail, historic urban grids, and redevelopment momentum. Brick Church Station’s major redevelopment demonstrates what’s possible, but that project required complex negotiations and unique financing. A Florida-style law would make similar projects routine, not one-off exceptions. Newark’s TOD overlays show strong intent, but administrative approvals and parking reform would allow those overlays to scale.

In both cities, corridors like MLK Drive, Broad Street, Main Street, and Freeway Drive already have the bones for walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods. The policy change simply clears the path.

Direction From Here

Newark and East Orange do not need new infrastructure to add thousands of mixed-income homes and active ground floors near transit—they need predictable rules. Florida has shown that statewide by-right entitlements for mixed-income housing on commercial land, paired with parking reform and a simple tax tool, can unlock this potential rapidly. If New Jersey applied the same framework here, these corridors would be among the first to benefit.

All legal mechanics referenced above are drawn from Florida Statutes §§125.01055, 166.04151, 196.1978, and 196.1979 (as amended in 2024) and applied hypothetically to Newark and East Orange transit corridors.

My Non-negotiables for Picking a Residential Development Site

In real estate development, site selection is where everything begins, and where most projects live or die. Over the years, I’ve walked hundreds of parcels, sat through countless planning board meetings, and pushed deals across the finish line. Through all of it, I’ve narrowed my approach down to a few core criteria that separate viable opportunities from expensive distractions. These aren’t just “nice to have.” They’re essential for financial performance, resident retention, and long term neighborhood fit.

Rents That Are Steady and Predictable

Before anything else, the deal has to pencil. That starts with understanding the rent profile of the neighborhood and where it can go, not a glossy broker version. I avoid overheated submarkets where rents shoot up too fast and tenants are stretched thin. That volatility leads to turnover, vacancies, and bad assumptions. I look for areas with consistent, sustainable rents that reflect real income growth and a solid tenant base, including C and D markets where working professionals and families who value quality space could be enticed to live. A lot of times, these are areas that banks and other financial partners aren’t interested in lending in. I’ll pull comps, absorption data, and lease histories to project yields based on reality, not wishful thinking. If the underwriting relies on aggressive rent bumps to make the numbers work, it’s usually a pass.Walkability to Daily Amenities

Location isn’t just about a pin on the map. It’s about how people live day to day. I prioritize sites where residents can handle their daily routine on foot, with a grocery store, school, coffee shop, or park within a 10 to 15 minute walk. That kind of accessibility builds community, reduces car dependence, and gives a neighborhood real staying power. Sometimes that means bringing in the services myself. I do my own on the ground assessment, walking the neighborhood morning, noon, and night. Can you pick up groceries, make dinner, catch mass transit into the city, and meet a friend for a drink without getting in a car? Do I feel safe enough and do I see it getting better? If the answer is yes, retention goes up and leasing velocity follows.A Healthy Tree Canopy

It sounds like the urban planner in me, but tree cover is a powerful signal. Street trees correlate directly with neighborhood investment and livability. During site walks, I pay close attention to shade, canopy density, and the general feel of the streetscape. Blocks with mature trees invite pedestrian activity, increase comfort, and usually indicate stable, better resourced communities. On the flip side, barren streets often point to deferred investment and a tougher road through approvals and leasing. Trees don’t just look good, they drive property values, cool urban heat, and signal a neighborhood people want to be in. One thing I’m known for in every project I do is hiring a master arborist and including street trees in all of our site plans.Access to Third Places

Every strong neighborhood has spaces where people connect beyond home and work. As Richard Florida noted in The Rise of the Creative Class, informal gathering spots like cafés, gyms, bookstores, and neighborhood bars build social capital and anchor communities. In a hybrid work world, proximity to these places isn’t fluff, it’s a leasing advantage. I map nearby options to ensure residents have places to meet, socialize, and build connections. These anchors reduce turnover, drive word of mouth leasing, and create neighborhoods people want to stay in.

Good site selection blends hard data with boots on the ground intuition. By holding firm on these four criteria, rents, walkability, trees, and third places, I’ve been able to build projects that perform financially and genuinely strengthen their surroundings. I hope to keep doing so for as long as I can.

Common Sense Advice on Contracts for Architects to Avoid Uneccesary Lawsuits

https://norrismclaughlin.com/blogs/general-firm-blog/category/im-architect-can-protect-liability

“As an architect and design professional, you want your vision for what the client needs and wants to become a tangible reality. My knowledge of architects arises not only from 30 years of practice in construction law, but from my experience at Columbia College, my alma mater, back in the early 80’s when I was a clerk at Avery Library – to many, the best architectural library in the country. There I met and befriended many architectural students and graduates who showed me that architecture is as much an art as it is a science. Architects are special people – artists really – because they have an uncanny ability to see things in multiple dimensions and amazingly, they are able to turn concept and energy into matter.

But then we step down to the sometimes unpleasant reality of construction risks and legal exposure that every engagement or project brings.”

Sustainability and Infrastructure

Walking along Bidwell Avenue in Bergen Lafayette the other day, I noticed something that most people would probably overlook. The street had been freshly repaved, the pavement seams were clean, and traffic flowed without the jarring dips and patched trenches that so often linger after utility work. It was the result of the Jersey City Municipal Utilities Authority’s emergency sewer replacement project along Garfield Avenue from Bidwell to Fulton, which included new water mains, sewers, and gas lines. The work wasn’t glamorous, but it was done right, and the difference was immediately visible at street level.

JCMUA’s quiet, consistent role in maintaining water quality, stormwater systems, and aging underground infrastructure is easy to miss. But their efforts are essential to keeping older neighborhoods functioning day after day. In a city where many systems were built for smaller populations and a different climate, this kind of maintenance underpins everything happening above ground.

My own path in historic adaptive reuse began years ago, walking blocks to document buildings for historic district designations and restoration efforts. Over time, I’ve worked on expanding districts and restoring historic churches throughout the country. Those experiences have taught me that the health of a neighborhood depends as much on what’s beneath the surface as on what stands above it.

Jersey City-from Hamilton Park to Bergen Lafayette, Greenville, and Journal Square are built on a historic urban layout: narrow streets, dense buildings, and mixed uses layered over more than a century of change. The infrastructure beneath these neighborhoods was never designed to support today’s population or environmental pressures. When water mains burst or sewers back up, it doesn’t stay below ground. Businesses lose revenue. Commutes are delayed. Buildings are damaged. Daily life is disrupted. Over time, repeated failures quietly chip away at residents’ confidence in their neighborhood’s stability.

Preservation is often associated with façades and architectural details, but true preservation requires modern infrastructure. Sewer and stormwater upgrades, like the work completed on Bidwell Avenue, are critical to protecting historic building foundations, preventing flooding, and allowing these neighborhoods to grow without losing their character. Recent developments abound in Jersey City, but none of it works without reliable infrastructure beneath it.

In Greenville, flooding remains a real threat. The storms of July 2025 brought flash flooding across Hudson County, prompting a state of emergency. Nor’easters underscored how vulnerable these neighborhoods can be. Sewer upgrades increase drainage capacity, protecting properties and keeping streets passable during increasingly frequent extreme weather events.

JCMUA’s continued projects, including upcoming sewer main repairs on Lexington Avenue, reflect the kind of steady work that keeps these systems functioning. Infrastructure investment isn’t separate from preservation; it’s a prerequisite for it and should be supported. The sidewalks, storefronts, and streetscapes that define Bergen Lafayette, Greenville, and Journal Square rely on what’s happening below ground. If we want these neighborhoods to thrive for another century, we have to care as much about the pipes and tunnels as we do about the cornices and façades.

Second Chances and the Afterlife of Former Churches

Once symbols of faith and community, many Roman Catholic churches across New Jersey now stand in quiet transition, their stained glass catching light for a different congregation entirely. Across the country, deconsecrated churches have been reborn as restaurants, hotels, residences, breweries, and event venues. But in the dense, heavily regulated world of the metropolitan region, such transformations are as much about negotiation and identity as they are about architecture.

In Jersey City, a 19th-century church on Pacific Avenue was reimagined as Lafayette House, a residential conversion that preserved its Gothic facade and arched windows. Nearby in Lincoln Park, the former sanctuary of a local parish now hosts Arca, an Italian restaurant that serves handmade pasta beneath vaulted ceilings once filled with hymns. Across the Hudson, Brooklyn and the Bronx have seen similar reinventions, with developers squeezing new life into old sanctuaries that once anchored their neighborhoods. Nationally, the Hotel Peter and Paul in New Orleans, housed in a former Catholic complex of church, rectory, and schoolhouse, has become a benchmark for this new genre of reuse, its altar now a stage for events rather than sacraments. The Church Brew Works in Pittsburgh has poured beer from tanks placed directly on the altar for nearly thirty years, keeping the pews intact and the stained glass glowing. But such transformations come at a steep cost.

Converting sacred architecture into commercial or residential use demands creativity and capital. Churches were built for reverence, not rent rolls. Their vast open naves and steep roofs resist easy subdivision. Plumbing and mechanical systems must be threaded through masonry walls built before electricity, let alone air conditioning. Deferred maintenance, water damage, and decayed glass and stone are common. And once the tax exemption falls away, utilities, insurance, and assessments quickly add up. Bureaucracy adds another layer. Zoning boards must grant use variances, historic commissions must sign off on design changes, and diocesan offices—all the way up to the Vatican, must formally deconsecrate properties before sale. The Catholic Church also requires that altars and sacred relics be removed or destroyed, a ritual reminder that these spaces were once considered holy.

Community reaction is rarely uniform. Some former parishioners welcome the idea that their old church is being saved from decay, while others recoil at the thought of cocktails in the nave. In places like Jersey City or Newark, where congregations once reflected immigrant waves now scattered or diminished, the debate becomes less about theology than about ownership of local memory. A few self-appointed experts often surface during these discussions, lamenting the loss of heritage through rumor and innuendo but offering few practical solutions. Their commentary can blur facts and slow projects that, handled carefully, might otherwise preserve much of what they claim to value.

The best redevelopments, by contrast, treat preservation as a form of collaboration, not opposition. They stabilize structures, maintain facades, and invite the public back in, even if under different terms. The architecture, stripped of its liturgy, finds new use in the rituals of modern urban life: dinners, performances, celebrations, and commerce. In these spaces, faith gives way to continuity, and continuity is its own kind of grace.

Local Business Keeps Local Dollars

As an urban planner, I understand the vital role that local businesses play in creating and sustaining vibrant communities. Local businesses are the backbone of our neighborhoods, and they provide a range of economic, social, and cultural benefits. In this blog post, I want to explore why local businesses keep money in the community, and why that is important for the health and well-being of our communities.

First and foremost, local businesses are more likely to source their products and services from other local businesses. This creates a multiplier effect, where money spent at a local business circulates through the local economy, creating jobs and generating additional economic activity. This means that when you spend money at a local business, more of that money stays in the community, supporting the local economy and creating a virtuous cycle of economic growth.

Moreover, local businesses are more likely to pay their employees a living wage, which means that the money earned by those employees is more likely to be spent in the local community. This helps to further support the local economy and create a more prosperous and resilient community.

In addition to the economic benefits, local businesses also contribute to the social fabric of our communities. They provide a sense of identity and character to our neighborhoods, and they create opportunities for social interaction and community building. Local businesses are more likely to sponsor community events, donate to local charities, and support local schools, which helps to strengthen the social bonds within our communities.

Furthermore, local businesses are more likely to be environmentally sustainable, which can have a positive impact on the health and well-being of our communities. They are more likely to use eco-friendly products and practices, which can help to reduce waste and pollution and promote a healthier environment for residents.

In conclusion, local businesses are a critical component of vibrant and resilient communities. They create jobs, support the local economy, contribute to the social fabric of our neighborhoods, and promote environmental sustainability. By supporting local businesses, we can help to build stronger and more connected communities, and create a more sustainable and equitable future for all.

Ethics in Architecture

Ethics and integrity in urban planning efforts

As an expert architect and urban planner, I have seen the significant impact that multifamily developments can have on the communities they are built in. While these types of developments provide much-needed housing, they can also present a number of ethical concerns that need to be addressed. In this blog post, I will discuss the ethical considerations that should be taken into account when planning and designing multifamily developments.

Accessibility and inclusivity: When designing multifamily developments, it is important to ensure that the building is accessible to all individuals, regardless of their physical ability. This includes designing for wheelchair accessibility, providing appropriate signage and wayfinding, and incorporating assistive technology where necessary. Additionally, inclusivity should also be considered, such as designing spaces that are welcoming to people of all ages, genders, and cultures.

Environmental sustainability: The construction and operation of multifamily developments can have a significant impact on the environment. As such, it is important for developers to prioritize sustainability in their planning and design. This includes using environmentally friendly building materials, designing for energy efficiency, and incorporating green spaces and other features that support sustainable living.

Community engagement: Multifamily developments can have a significant impact on the communities they are built in. As such, it is important for developers to engage with the community early on in the planning process to ensure that their needs and concerns are addressed. This can involve holding public meetings, conducting surveys, and working closely with local stakeholders to ensure that the development is a positive addition to the community.

Affordable housing: One of the primary benefits of multifamily developments is that they can provide affordable housing options for individuals and families. However, it is important to ensure that these developments are truly affordable and accessible to low-income households. This may involve working with local government agencies or nonprofits to provide rent subsidies or other financial assistance to those in need.

Safety and security: When designing multifamily developments, safety and security should be a top priority. This includes designing for fire safety, ensuring that the building is structurally sound, and providing appropriate lighting and security measures to prevent crime.

Ethical business practices: Finally, it is important for developers to ensure that they are engaging in ethical business practices throughout the planning and development process. This includes treating workers and contractors fairly, avoiding corruption and bribery, and being transparent in their dealings with local government agencies and other stakeholders.

In conclusion, multifamily developments can provide much-needed housing and other benefits to communities. However, it is important for architects and urban planners to consider the ethical implications of these developments and to work closely with local stakeholders to ensure that their needs and concerns are addressed. By prioritizing accessibility, sustainability, community engagement, affordability, safety, and ethical business practices, we can create multifamily developments that are truly beneficial to all.

Learning from your mistakes

It all begins with an idea.

As a 30-year real estate developer, I have made my fair share of mistakes. But I can honestly say that those mistakes have been some of the most valuable learning experiences of my career. In this blog post, I want to share with you the importance of learning from your mistakes, and how it can ultimately make you a better real estate developer.

First and foremost, mistakes are inevitable in any field, especially in real estate development where there are so many moving parts and variables to consider. But it's not the mistakes themselves that define us, it's how we respond to them. When you make a mistake, it's important to take responsibility for it, learn from it, and move forward.

Learning from your mistakes can help you to identify areas where you need to improve, and to develop new strategies and solutions for tackling future challenges. For example, if a project fails to meet its budget, you can use that experience to improve your cost management skills and to develop a more accurate budgeting process for future projects.

Moreover, learning from your mistakes can help you to build resilience and adaptability. In real estate development, the landscape is constantly changing, and what worked in the past may not work in the future. By embracing your mistakes as learning opportunities, you can develop the ability to pivot and adapt to new challenges, which is essential for success in this industry.

In addition to personal growth, learning from your mistakes can also help you to build trust and credibility with your clients, partners, and investors. When you are transparent about your mistakes and show a commitment to learning from them, it demonstrates your professionalism and integrity, which can help to build long-lasting relationships and partnerships.

In conclusion, learning from your mistakes is an essential part of growth and success in real estate development. Instead of fearing mistakes, embrace them as opportunities for growth and improvement. Take responsibility for your mistakes, learn from them, and use that knowledge to become a better developer. Remember, the road to success is never a straight line, but it's the detours and bumps along the way that make the journey worthwhile.

Home ownership and Strong Communities

It all begins with an idea.

As a real estate developer, I have seen firsthand the impact that homeownership can have on communities. Homeownership is not just a personal investment, but also a social and economic investment that supports strong communities. In this blog post, I want to explore the importance of homeownership and how it can contribute to the well-being of communities.

First and foremost, home ownership promotes stability and long-term investment in a community. Homeowners are more likely to stay in their homes and invest in their properties, which helps to maintain property values and create a sense of stability in a neighborhood. This stability can have a positive impact on the quality of life in a community, including better schools, lower crime rates, and increased civic engagement.

Moreover, home ownership helps to build wealth and financial stability for individuals and families. A home is typically the largest asset that a person or family will own, and it can provide a source of financial security and stability for generations. Additionally, home ownership can provide access to a variety of tax benefits and incentives, such as the mortgage interest deduction, which can help to offset the cost of home ownership and support long-term financial stability.

Home ownership can also help to promote a sense of pride and responsibility in a community. Homeowners have a vested interest in the well-being of their community and are more likely to be involved in local events and initiatives. This sense of pride and responsibility can help to foster a strong community spirit and a sense of connectedness among residents.

Furthermore, home ownership can be a powerful tool for building equity and bridging the wealth gap. Home ownership can provide a pathway to economic mobility for historically marginalized communities, including people of color and low-income households. By providing access to affordable home ownership opportunities, we can help to create a more equitable and just society.

In conclusion, home ownership is an essential component of strong communities. It promotes stability, builds wealth, fosters pride and responsibility, and helps to bridge the wealth gap. As real estate developers, we have a responsibility to create housing opportunities that support home ownership and contribute to the well-being of our communities. By prioritizing affordable home ownership opportunities, we can help to create strong, vibrant, and resilient communities for generations to come.